Links to various Aetna Better Health and non-Aetna Better Health sites are provided for your convenience. Aetna Better Health of California is not responsible or liable for non-Aetna Better Health content, accuracy or privacy practices of linked sites or for products or services described on these sites.

Our neighborhood health story: How one Florida county is sowing seeds of success among its youth

By Bonnie Vengrow

By Bonnie Vengrow

From the series

"Our neighborhood story"

Voice/on screen text: Steven Heflin, Bannerman Student

Whenever you go from a classroom to the garden, it’s like a weight being lifted off you. It’s really nice, it’s calming, it’s relaxing, and it’s just beautiful walking out into a garden.

Voice/on-screen text: Annie Sheldon, UF/IFAS Agent, Family and Consumer Sciences

Our hopes with the school garden here at Bannerman is to connect the community with agriculture, and also educate them on some practices they could use at home.

It just gives them a kind of peaceful place to go to and get out some of that anger, frustration that may happen in their day to day lives as students. So just kind of brings in that sense of serenity and peacefulness, and helps them express themselves through a different venue.

Voice: Steven Heflin, Bannerman Student

The point that I realized that it was nice was whenever we started harvesting everything. Cause then they told me that I could bring as much food as I wanted home. So I was like, ‘Oh, man! This is great! (laughs)

Voice/on-screen text: Glenn Thigpen, UF/IFAS Extension Master Gardener Volunteer

We’re trying to not only change the way they look at food and how they might be able to provide it for their family, but the opportunities that they can have that they might not see.

What I hope is for the students to learn that there’s somebody that is not an authority figure, there’s somebody that took their time to work with the students, to try and teach them not only about gardening, but that somebody cares about them. That’s mainly what I feel like we’re here for.

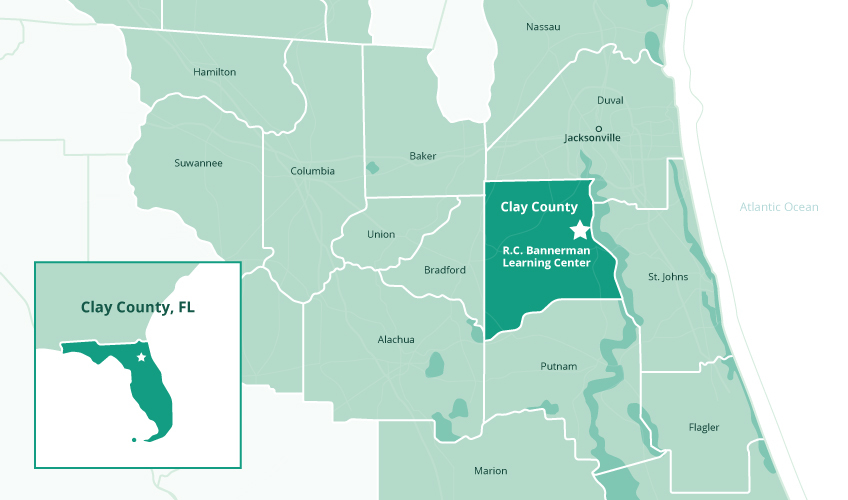

Your community shapes how long and how well you live. The U.S. News & World Report recently teamed up with the Aetna Foundation to rank counties across the U.S. on factors like education, nutrition, public safety and more. Out of 3,000 counties ranked, we identified the top 500 healthiest communities rankings. Here, we profile R.C. Bannerman Learning Center in Clay County, FL. The county has an overall health score that’s 12 points higher than the national average, but even the healthiest communities have room for improvement. In this series, we take a look at places on the list where members of the community have identified a health challenge and are working to solve it with the help of a grant from the Aetna Foundation. Here, we profile a Clay County school that’s going above and beyond to provide mind and body health for its students.

Steven H. never considered himself much of a student. The 16-year-old Clay County, FL, native would much rather work with his hands than do homework. But homework became more interesting about a year ago, when he enrolled in R.C. Bannerman Learning Center and began making weekly trips with his science class to the school’s garden.

With help from garden volunteers, Steven has learned how to cultivate many of the fruits and vegetables he loves, including broccoli, onions, radishes and peppers. As he’s planting, weeding and harvesting, he’s also seeing concepts from class come to life right before his eyes. And that motivates him to want to learn more.

Getting a teenager excited about school is a significant accomplishment, but perhaps even more so for the teachers at Bannerman. The only alternative school in the district, it educates about 220 students in grades 6 through 12. A majority of the kids have discipline or behavioral issues or are severely disabled. Many struggle to sit at their desks or focus during the 50 minutes of class time.

But in the garden, they thrive. Besides learning the basics of horticulture, they also pick up skills they’ll use the rest of their lives.

Encouraging hands-on learning

Master Gardener volunteer Amy Morie and ninth grader Bianca M. check the plants growing in the new Verti-Gro hydroponic system.

It’s not a leap to say that working outside with plants can be a positive influence on kids. Studies have linked garden-based learning to academic success, especially in science and math. Bannerman staffers notice how students seem calmer and more focused in the class after being in the garden, which in turn helps set them up for better learning.

For the last 20 years, the school has teamed up with the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Extension Clay County and its Master Gardener volunteers to create a spot where hands-on learning can take place. It’s entirely student-led: the kids are assigned bins, decide what they want to grow and are in charge of caring for the plants. “The garden is like a real-world lab,” says Amy Morie, who has volunteered in the garden for the last two years. “It gives our youth experience-based learning opportunities and helps them explore science, technology engineering and math (STEM) through nature, agriculture, horticulture and more.”

It helps that Bannerman teachers have also started using the garden to explain concepts introduced in the classroom. Science teacher John Coleman has revamped his curriculum so more lessons are tied to his students’ work in the garden. Culinary teacher Theresa Boring plants cilantro, onions, tomatoes and peppers, which her chefs-in-training harvest to prepare fresh salsa. Carpentry teacher David Rochester leads his students in designing, measuring, and constructing various structures in the garden.

The opportunities for learning expanded even more this spring, thanks to a grant from the Aetna Foundation that allowed students to install three new types of hydroponic systems and construct a shade structure to allow for year-round growing. The grant also funds the extension’s agricultural education efforts in area 4-H clubs and an after-school program for younger students.

A new shade structure being built by the carpentry class will allow students to grow produce year-round.

The latest in urban agriculture, hydroponic systems feed plants with a steady flow of nutrient-enhanced water instead of soil. The benefits are many. Hydroponic gardens require less space, water and fertilizer than traditional gardens; there are fewer weeds, pests and diseases; and plants grow up to 50% faster to allow for more frequent harvests.

“We have a long tradition of investing in community- and school-based gardens. It’s important to put advances in urban agriculture within residents’ reach,” says Amy Aparicio Clark, managing director of community impact and strategy at the Aetna Foundation . “As we looked for ways to make healthy food more accessible to Clay County residents, we realized Bannerman’s hydroponics program presented an opportunity to do this efficiently and with significant involvement from students.”

Giving families a healthy start

Bannerman is in the county seat, less than 40 miles away from the hustle and bustle of Jacksonville and the historic beaches of St. Augustine. With its wide open spaces, friendly residents and easy access to the nearby St. Johns River, it’s easy to see why the area is experiencing a population boom.

Still, Clay County isn’t without its health challenges. Though it’s a historically a rural agricultural county, many residents lack access to fresh produce, says Annie Sheldon, an Extension Agent with UF/IFAS Extension Clay County who helps coordinate the gardening efforts at Bannerman. As with other parts of the country, healthy eating can be a challenge here. According to data compiled for the U.S. News Healthiest Communities rankings, roughly 75% of adults in the county aren’t consuming enough fruits and vegetables (slightly better than the national average of 79.2%); 10.7% have diabetes (national average is 9.3%); and nearly 30% of residents are considered obese (national average is 31%).

Students can take home whatever produce they grow.

School gardens, like the one at Bannerman, are widely seen as one way to get healthy food in the hands of those who most need it, starting with the students and their families. “So many of our students struggle with having fresh produce because in their homes, fresh produce is fairly expensive,” adds Coleman. “They may have never had fresh green beans or fresh fruit right off the tree.” He remembers an eighth grader discovering Swiss chard in the garden last year. “He took some home, cooked it himself, ate the entire thing, and came back saying how good it was. This was an eighth-grade boy, in the kitchen, cooking his own food!”

The garden provides students at Bannerman with a leg up when it comes time to enter the workforce. “The garden and the hydroponics towers are giving them skills they can use to get a job, whether it’s a job that requires a college education or a technical program that uses horticulture,” Sheldon says. “Hopefully, we’re giving them that knowledge and inspiring them to continue in that field. We want to connect youth with agriculture and new practices around urban agriculture. We’re trying to encourage them to think about the future and how we’re going to feed the world.”

Cultivating lasting relationships

For many students at Bannerman, the garden is an oasis of calm.

Bannerman’s garden is stunning—all tidy rows of crops and flowers, a dappled greenhouse, a large gazebo and a goldfish-filled pond. It’s the best-kept secret in Clay County and one of the best-loved spots on this 45-acre campus.

For many students, the garden is also a safe space free of judgment. The plants and the Master Gardener volunteers aren’t interested in how the kids ended up at Bannerman. They embrace students as they are. “This school creates such a sense of hope for kids,” says Addison Davis, superintendent of Clay County District Schools. “There are great mentorships here, especially with the Master Gardener program. They do so much for our learners in order to help them get on track and prepare to graduate with their cohorts.”

“The number-one mentoring program we have at the school is the Master Gardeners who come and work with the kids,” agrees Michael Elia, Bannerman’s principal. “It’s not just about learning science out there—it’s really about building relationships. Those gardeners are the most consistent people a lot of these kids have in their lives. As I see it, they’re basically teaching kids life skills through gardening.”

One of those skills is tenacity. “A lot of these kids don’t see things from start to finish,” he continues. “With gardening, they’re seeing something complete a cycle. This could inspire them to get what they need to get done at Bannerman and go back to their school a different person.”

Glenn Thigpen, a Master Gardener volunteer, sees that transformation occur often. She recalls the student with autism who struggled to adapt to a classroom setting but was fully engaged once in the garden. Or the student who didn’t relate to his peers but exceled at planting and caring for his vegetables—even going so far as to paint his own plant markers. And there’s the aloof student who asked to take a vegetable plant home and later couldn’t wait to share her excitement over how well it was thriving. “None of these things are huge,” Glenn says. “But we really feel like we’re making a difference one student at a time.”

Count Steven H. among them. Besides learning he had a knack for growing crops, he’s also discovered how much he enjoys being in the garden. During his time at Bannerman, it’s served as a respite from the chaos of the class. “Whenever you go to the garden, it’s like a weight being lifted off of you,” he says.

About the author

Bonnie Vengrow is a journalist based in NYC who has written for Parents, Prevention, Rodale’s Organic Life, Good Housekeeping and others. She’s never met a hiking trail she doesn’t like and is currently working on perfecting her headstand in yoga class.